Life Hacks I’ve Picked up from Death Notices

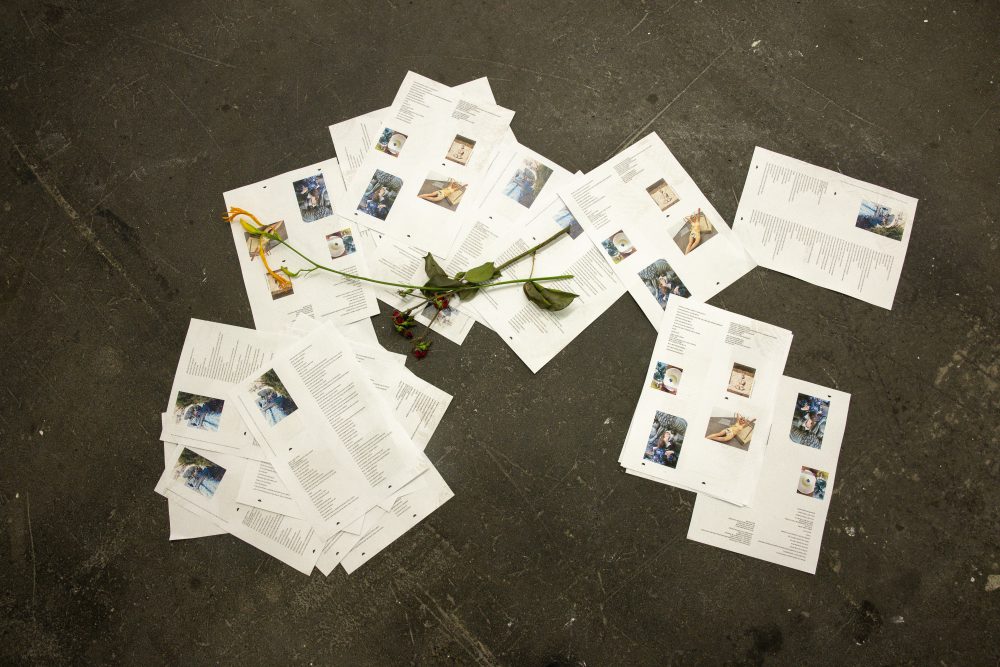

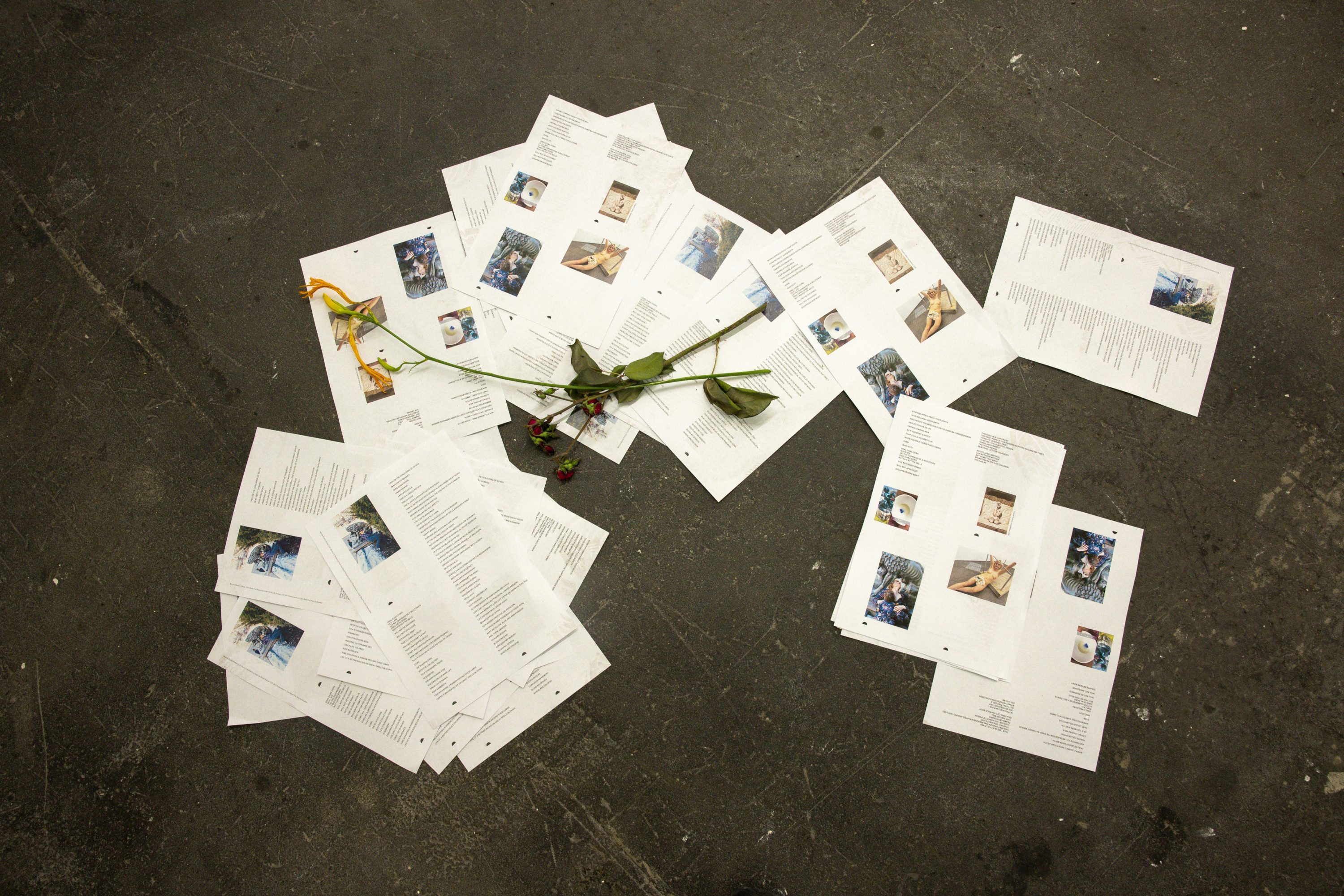

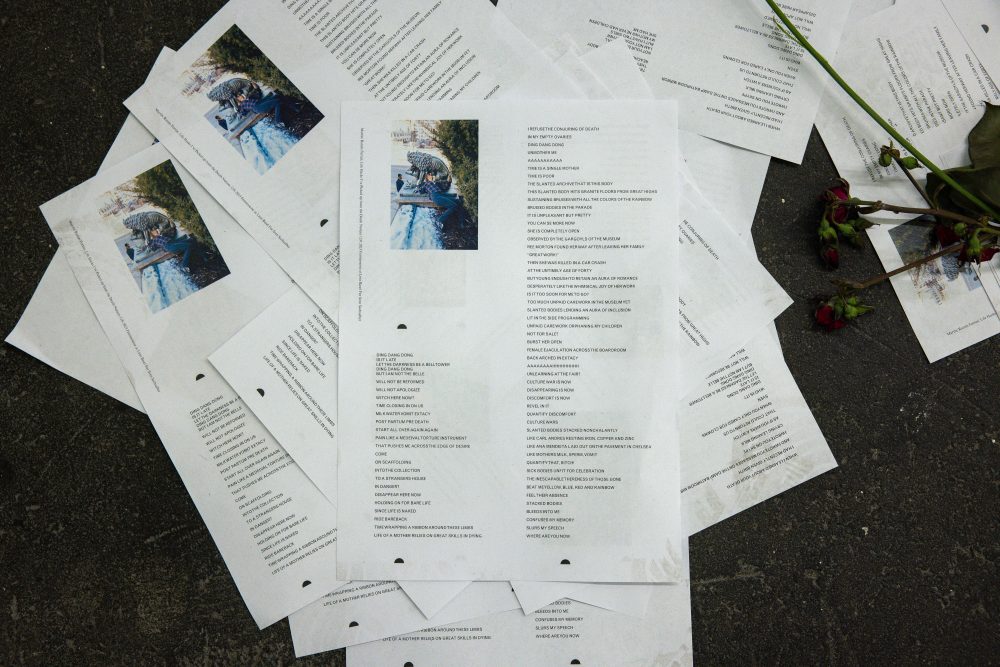

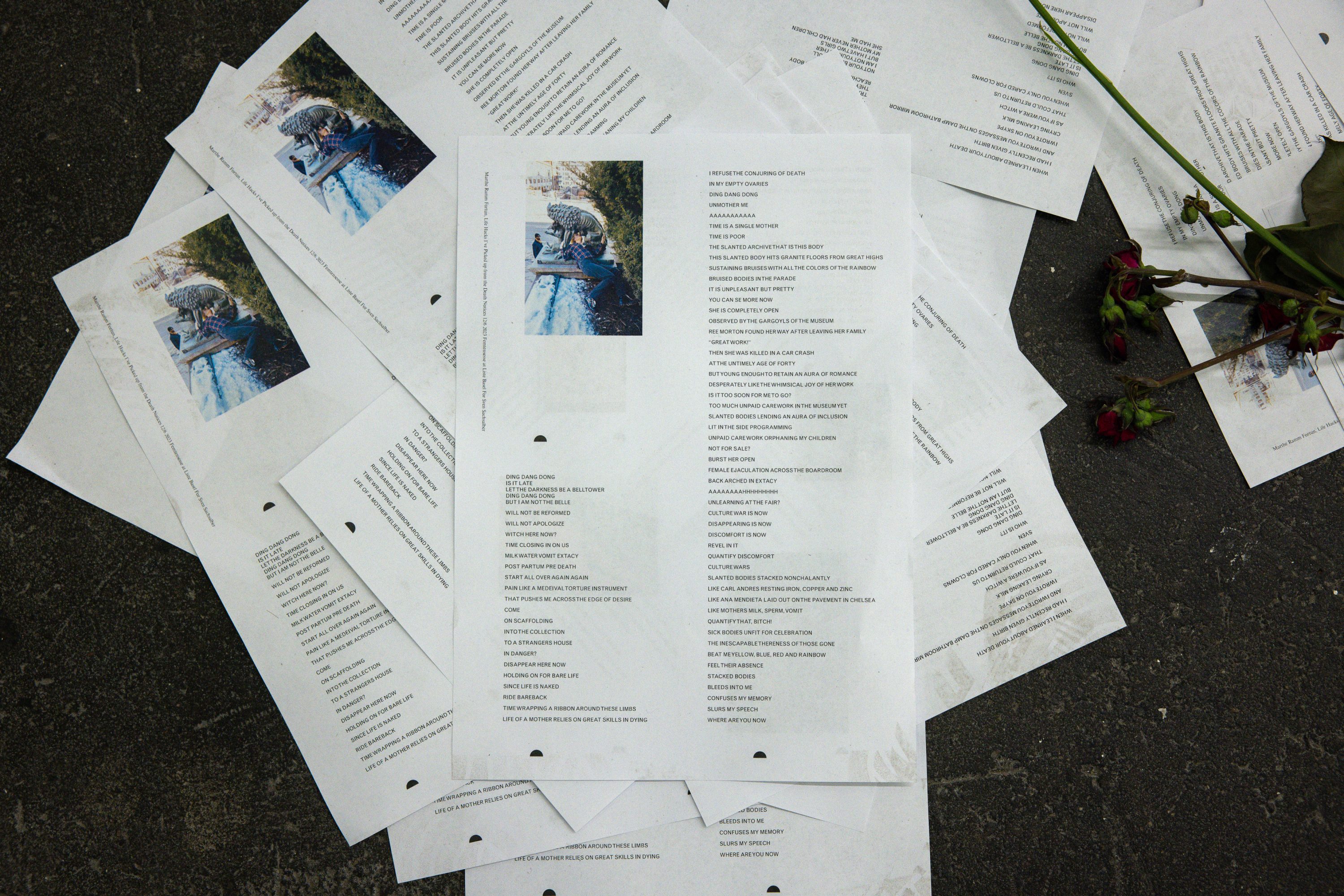

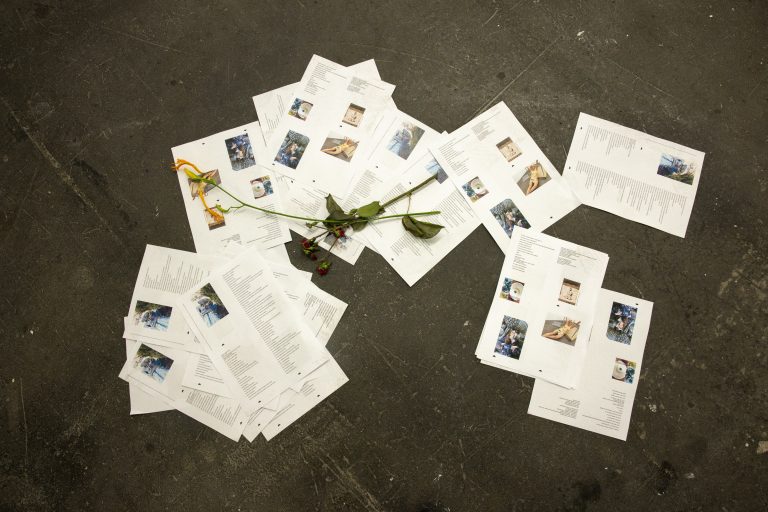

Femtensesse is thrilled to participate at Liste Art Fair Basel for the second time with a solo presentation of Norwegian artist Marthe Ramm Fortun, including three site-specific performances. Each performance starts in Femtensesse’s booth at Liste Art Fair at Messe Basel, Hall 1.1 before extending into public space.

Below follows a beautiful text on Fortun’s work written by Sinziana Ravini.

Marthe Ramm Fortun and the chase for new desires

« What does a woman want? » asked Freud in a letter to Marie Bonaparte. He never received a satisfying answer, but the question can be seen as a reaction to women’s resistance to their place in a patriarchal society. Women have always been an enigma, even to themselves, and when they do act according to their desires, sometimes too late, or too much, they often get stigmatized as “hysterics”, looking for a gaze, an interpretation, like Charcot’s famous Justine, Breuer’s Anna O, Jung’s Sabina Spielrein or Freud’s famous Dora. When the so-called hysterics start mastering the interplay of gazes and the eroticization of power relations, they usually get to be called “femmes fatales”, but who is killing who? Is there a possible passage from “la femme fatale” to “la femme vitale?”

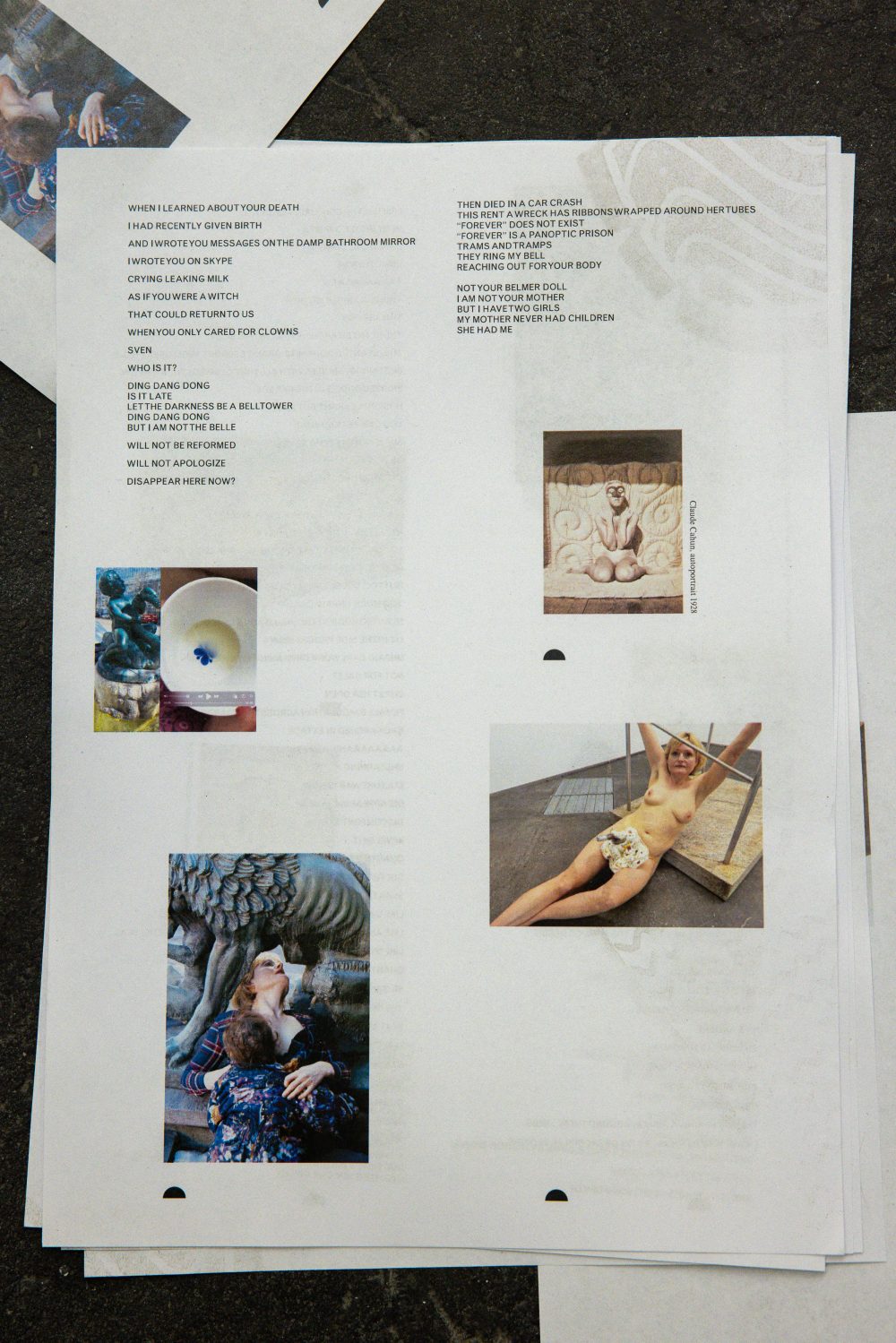

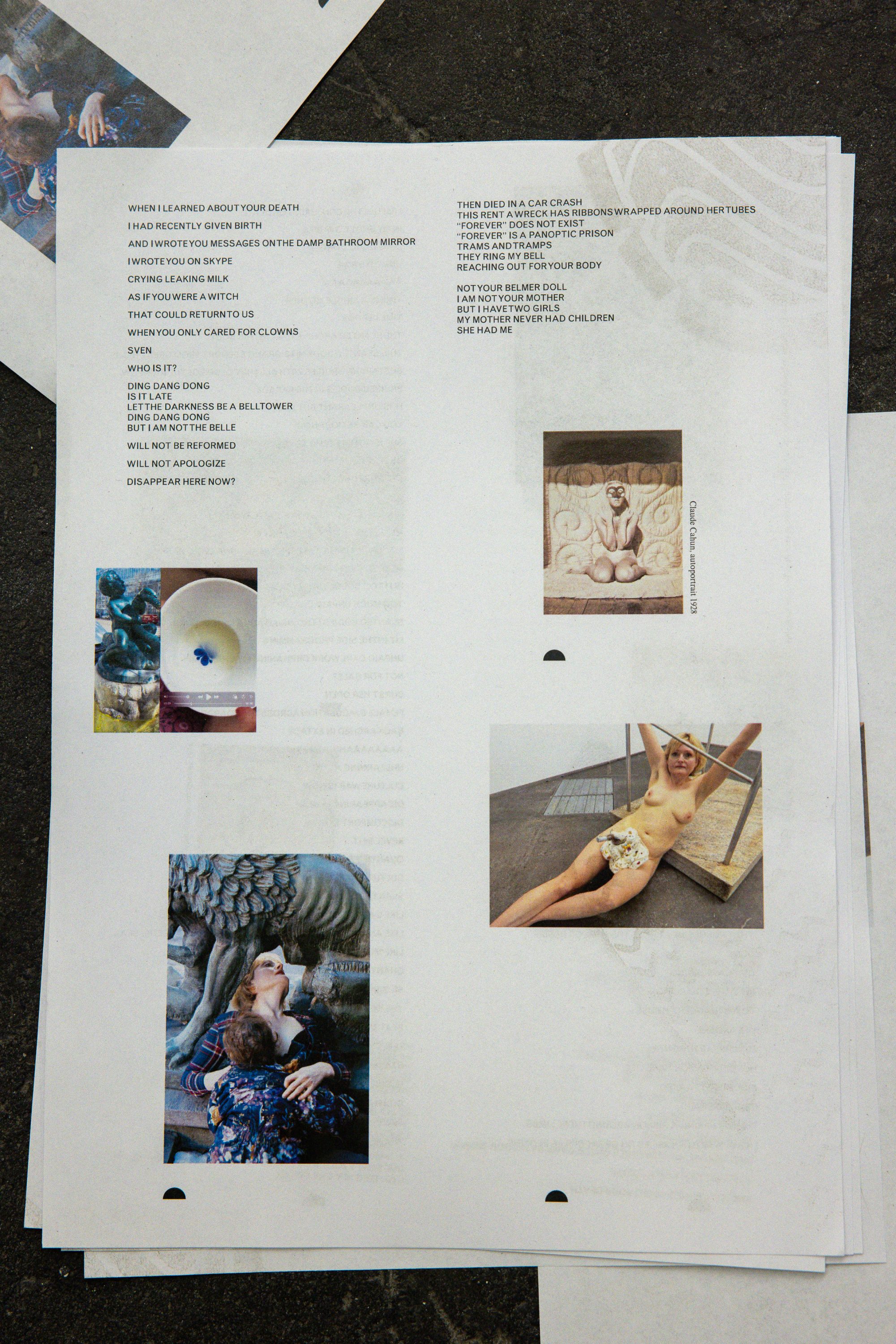

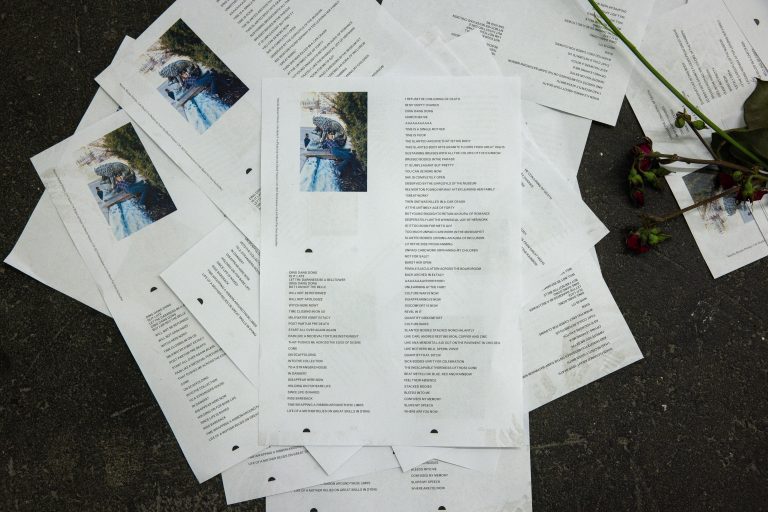

When I think back on Marthe Ramm Fortun’s stunning performance in Oslo some months ago, her ferocious embracement of the public space, half naked, half dressed in a green trench coat, with her blond windy hair shining like a torch, her erring and liquefying self-abandonment on the street, her sensual yet desperate interactions with lawns, roundabouts, fountains and ponds, reading out loud a beautiful, highly uncanny text that she was holding in her hands, as a lifebuoy, then seeing her give up, literary, falling and embracing the water with her body, fleeting as if she was dead, I think of Freud’s irritating question, I think of Hollywood’s femme fatales, now dead, unable to answer any question at all about their true desires, of Annika Elisabeth von Hausswolff’s terrifying photograph of a woman, in the 90-s lying dead in the reeds and her constant sliding between nightmares and desire, Sara Stridsberg’s Darling River and Antarctica of dreams, Stieg Larsson’s masochistic heroines who eventually get back at their perpetuators, star curators looking for Nordic Miracles, star critics pissing on their Nordic Miracles, but I also think of one of my strongest encounters ever with a work of art: Hamlet’s Ophelia painted by Millet.

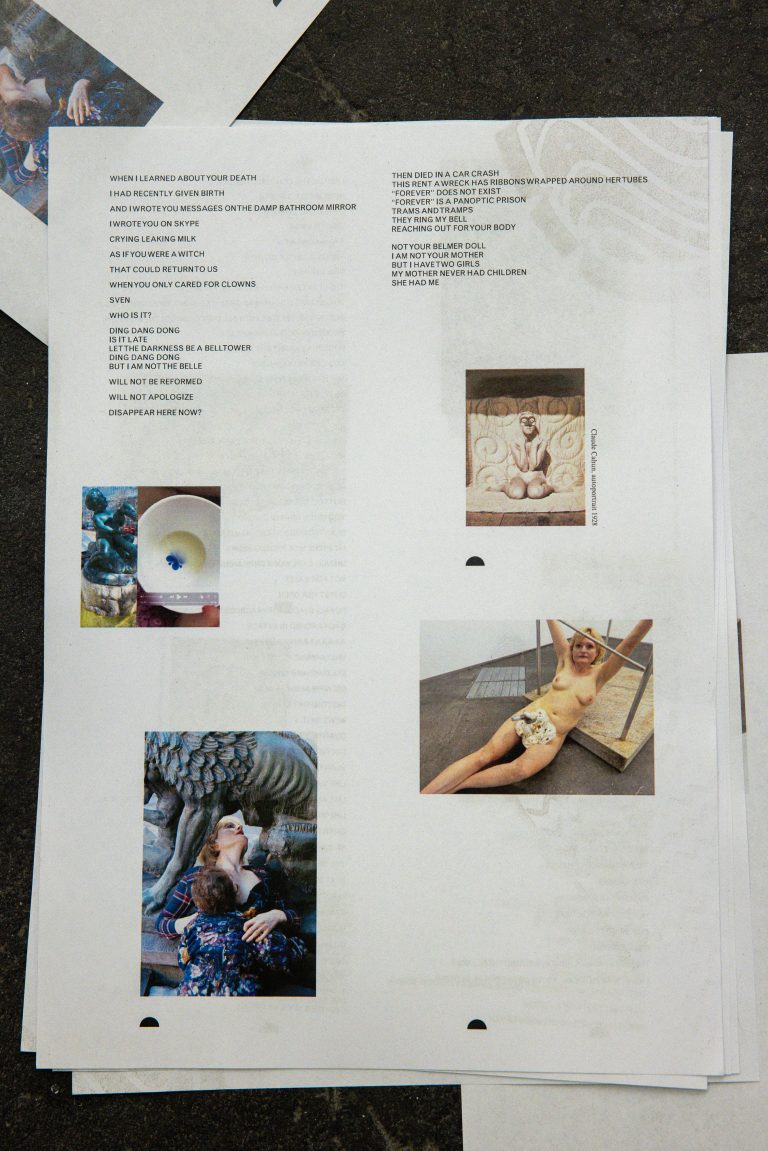

As a child in communist Romania, while losing myself for hours in artbooks, since there was nothing to watch on TV- other than Ceausescu’s eternal speeches to the nation, I used to come back again and again to this specific image. I didn’t understand why this beautiful creature named Ophelia was lying in the water with her clothes on, why her gaze was turned to the sky, her hands sticking out at the surface like water lilies, why she looked so immobile, when she was supposed to swim and have fun. Once when I finally understood, I immediately felt the drive to dive into the image to rescue her. That’s how images work, they always arrive too soon, or too late, cut from the original event while at the same time creating a new event within us, like strong works of art always do. Who is responsible for Ophelia’s death? Hamlet? Society? Herself? When Marthe embraced the water surface, with her face turned down in the waters, no one moved, since it was a performance. But as a beholder of her enacted helplessness, I immediately felt as an accomplice to the crime. If I would have dived down to help her out, I would have turned myself into a fool who doesn’t know the difference between the act and real life. At the same time, the disavowal of that very difference between art and life, truth and simulacra, right and wrong, is what makes Marthe’s work so strong and disturbing. She refuses to be only an object of desire, since she always turns our gazes inwards, with texts that reaffirm her as an acting and thinking subject. In the text that she read during her performance, Eros and Thanatos, sex and death-drive intertwines in an expression that doesn’t ask for permission: “water mirror / over the brain / forming eyes above the eyes / I sink into the water / merry now / water lilies do not grow here / but I open my legs / don’t ask for permission / don’t ask for forgiveness” and later on “she shall not be reformed / she shall not be corrected”.

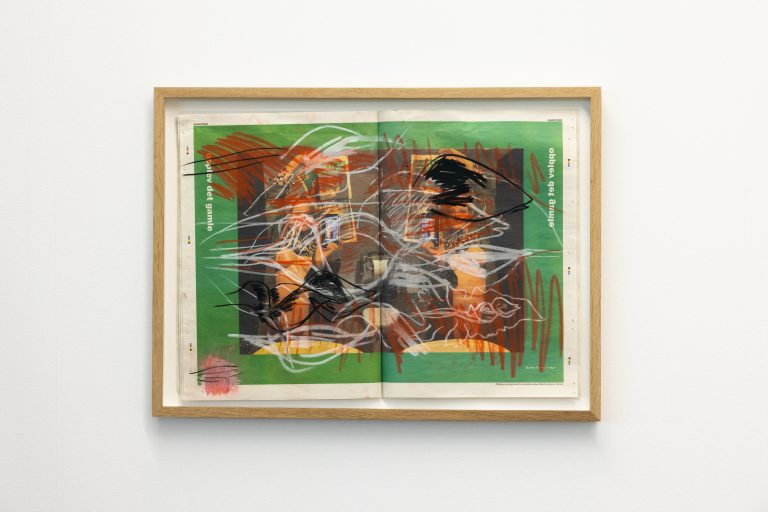

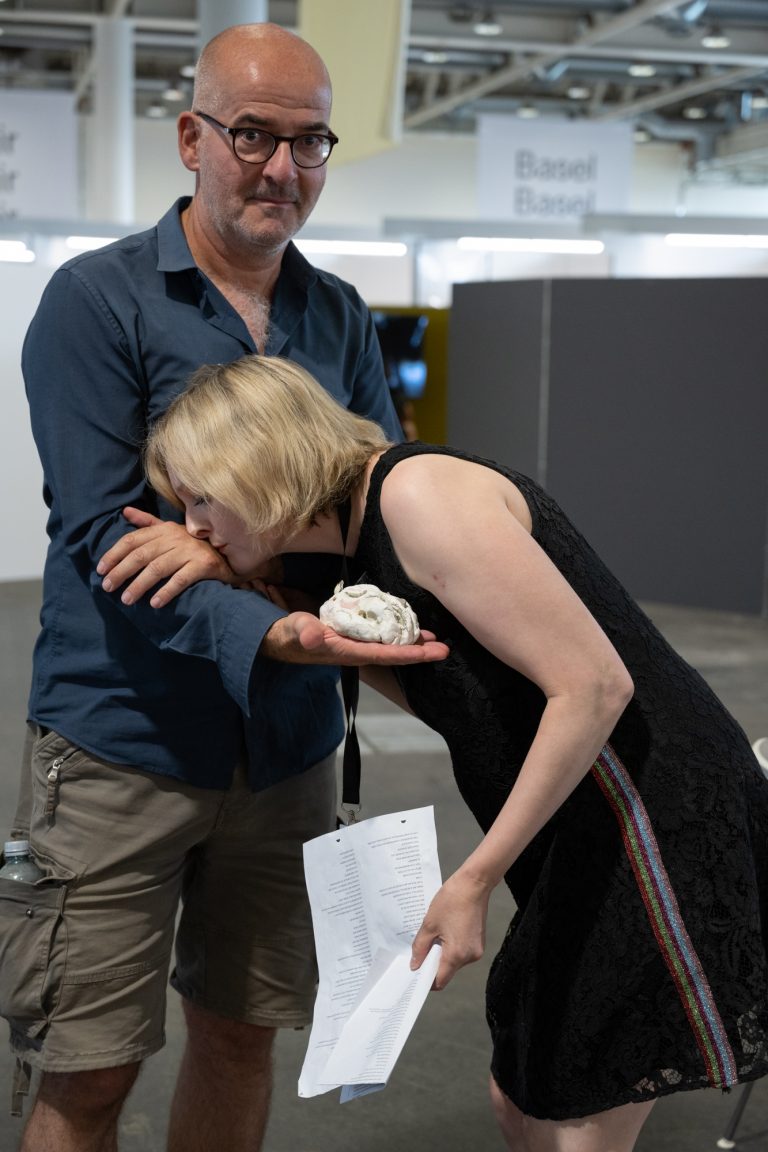

Georges Didi-Huberman writes in “Ninfa moderna” (2003) about the nymphs that played with the male gaze and how they were killed by that very gaze. Marthe’s playing with the gaze, all our gazes, is prolonging the rebellion of the nymph. In one of her performances “Seeing is Changing” (2018, Monnaie de Paris), while she performed with all kinds of so-called masterpieces, revealing her torso in front of Manet’s Olympia, she was thrown out by the guards despite the fact that she was a part of the official program. In order to finish her getting-naked performance, she had to take the audience to the WC. Duchamp, who famously turned the urinal into a desirable object, would have loved the way Marthe transforms the toilets in a place of artistic resistance to institutional powers, but also a place where the “obscene excess-supplement of the superego” – the injunction to enjoy in the midst of a conflict between the conscious and the unconscious, gets revealed, and in a way – suspended. But what is obscene, is not our transgression of the law, but our libidinal investment in the Law, claims Zizek, in “The Puppet and the Dwarf: The Perverse Core of Christianity” (2003). Marthe Ramm Fortun makes obscenity both desirable and fun to watch again, following the only true law – the law of desire.

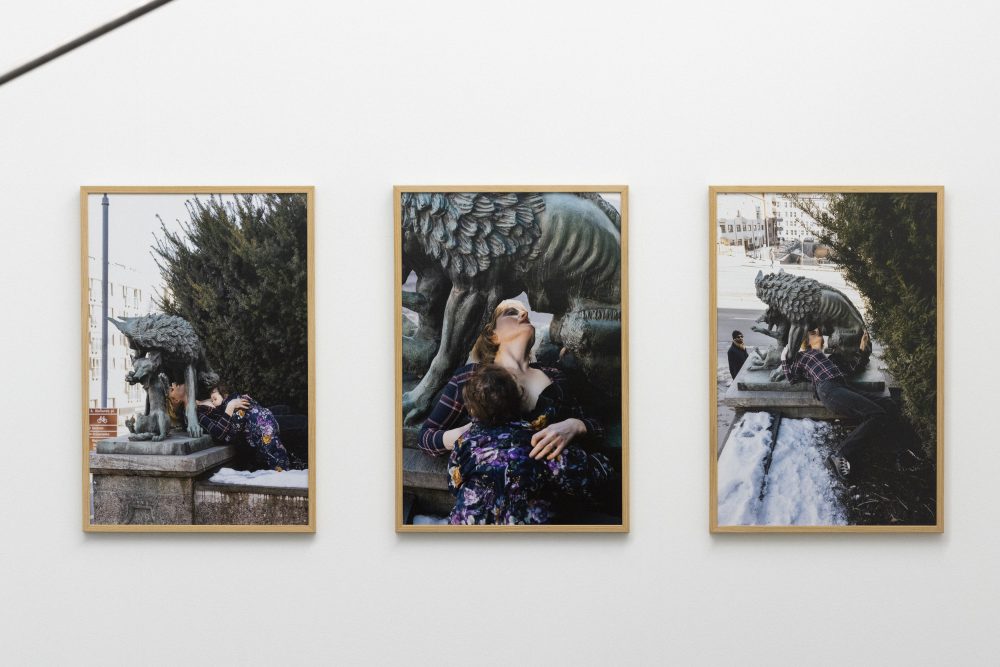

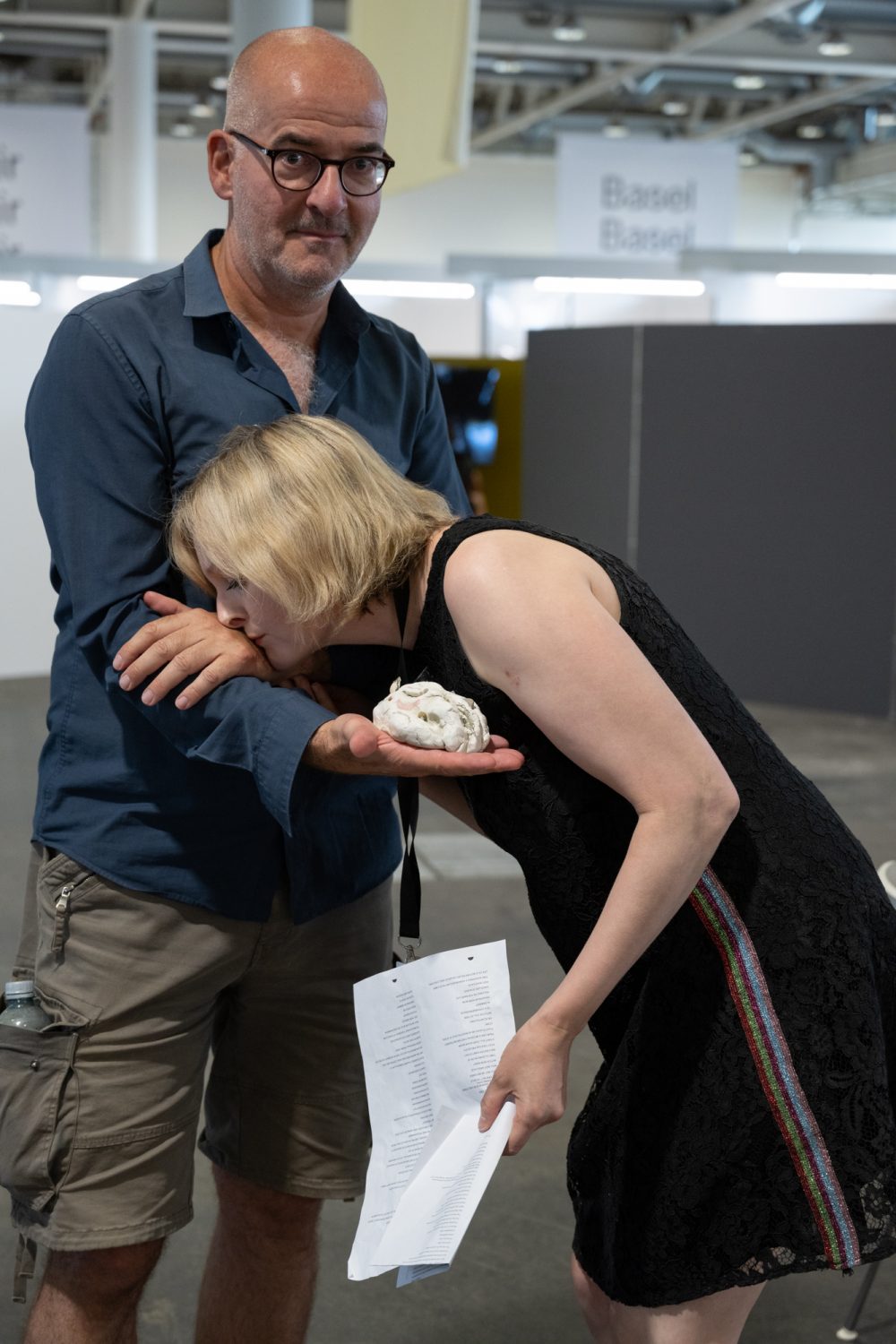

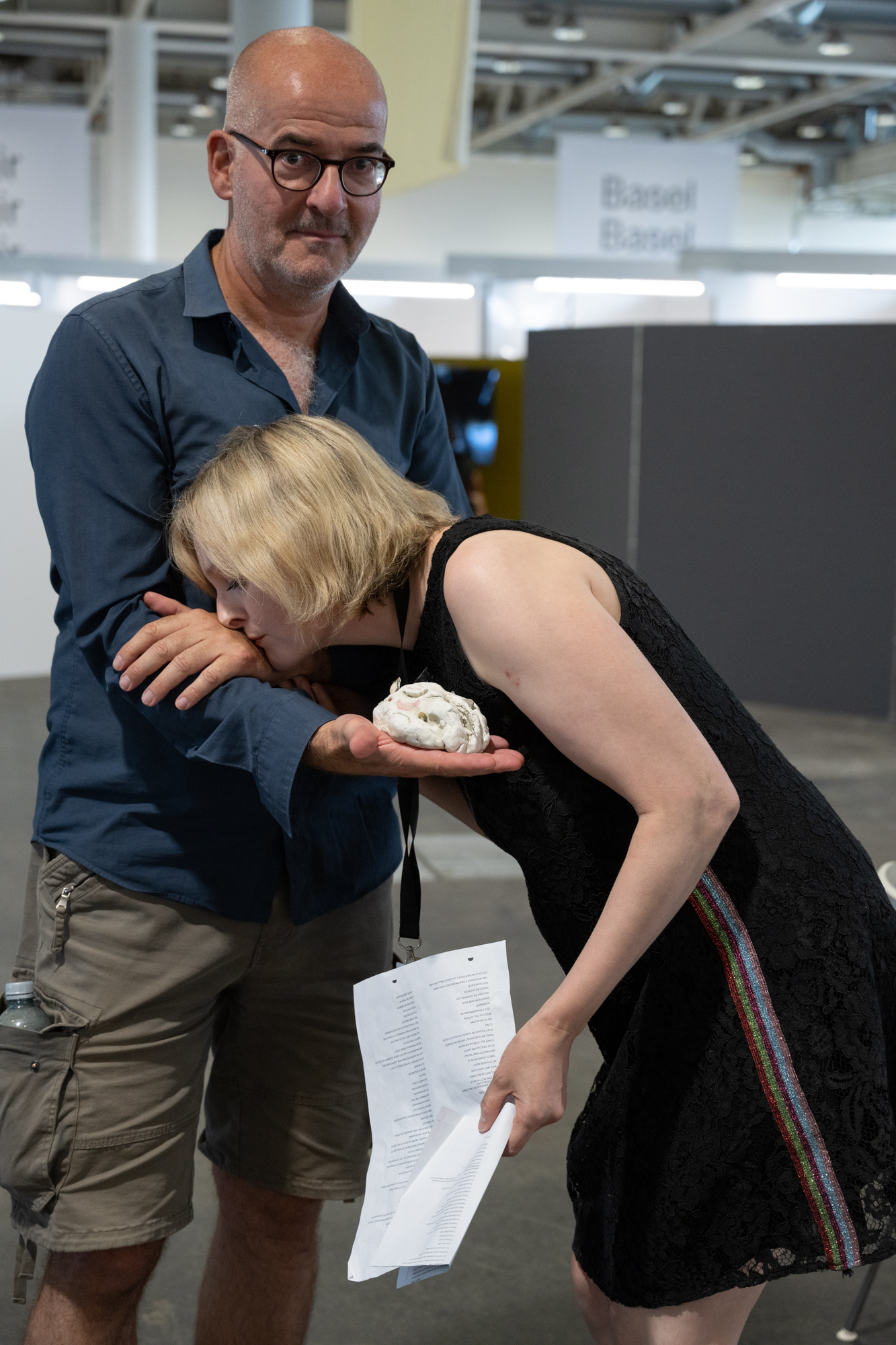

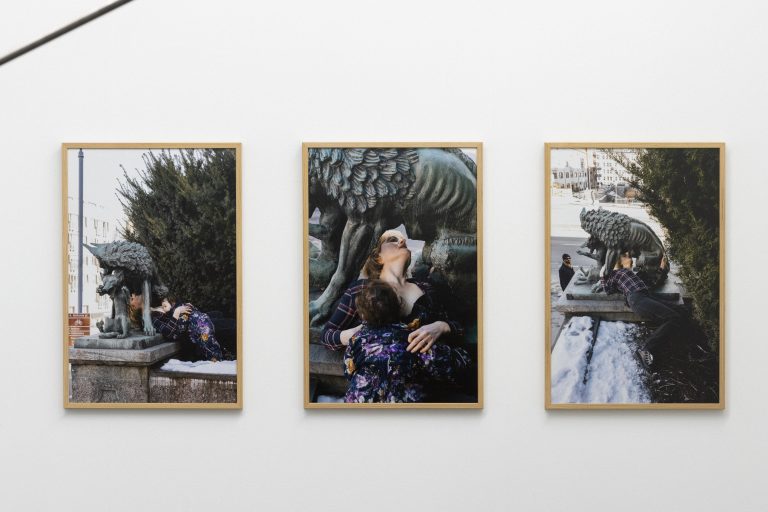

Eventually Freud did actually find an answer to his question, an answer which is less known, he said that what women actually want is motherhood. In one of her recent performances Marthe is playing the role of the rebellious mother who breastfeeds her child in the public sphere – perhaps one of the most disturbing things a woman can still do today. But Marthe, as a femme vitale, who has given life and enjoys the power of that very lifegiving, doesn’t disturb people in an expected way, doesn’t merge in a symbiotic, almost Christian love to her child. She embarks both her child and the beholder on a true adventure through the city, going as far as letting herself be breastfed by a statue, while she’s breastfeeding her child, thus creating a both funny and highly vertiginous mise en abyme. The classic Oedipal formula “sexual desire for the mother” gets transformed into “the sexual desire of the mother”, which in itself creates other triangular structures, other myths, other life hacks and fore and foremost – other desires.

– Sinziana Ravini, May 2023

Marthe Ramm Fortun (b. 1978, Oslo) lives and works in Oslo, Norway, where she is adjunct professor at the Oslo National Academy of the Arts. Fortun received her education from University of the Arts, London, New York University, New York and HISK – Higher Institute of Fine Art, Ghent. Recent solo exhibitions include Skriver for ikke å skade at Femtensesse, Oslo (2022); TA VARE! at Kunstnerforbundet, Oslo (2019); Stones to the Burden at The Munch Museum, Oslo (2016) and Skrive byen, skrive den om at UKS, Oslo (2014). Her work has been featured in numerous group exhibitions and biennials in Norway and abroad including Kistefos Museum, Jevnaker; Musée d’Art Contemporain, Montreal; Monnaie de Paris, Paris; Gladstone Gallery, Brussels; The Vigeland Museum, Oslo; Komplot, Brussels; Performatik, Brussels and Performa, New York. Current projects include ALL SHE LEFT BEHIND!, a museum acquisition of five performances at Henie Onstad Art Center, Høvikodden (2021- 2023); a new commission entitled All What Matters for The National Museum, Oslo (2022-2023); and We Shall Not Write Textbooks (2019-2029), a ten-year performance cycle for the project Minerva’s Voiceat the Museum of Natural History in Bergen, curated by Marit Paasche and commissioned by KORO – Public Art Norway.

With generous support from OCA – Office for Contemporary Art Norway and Billedkunstnernes Vederlagsfond

All images courtesy and copyright of the artist and Femtensesse